As ever, since the day we arrived here, it’s been up to us.

The racialized peoples of this hellish archipelago… to defend ourselves.

Let’s take a partial look at our collective histories of struggle…

In 1919, in Cardiff, Liverpool and East London racists targeted Chinese, Somali, West Indian (Caribbean), Malaysian, Egyptian and other racialized residents, many of whom were British colonial troops stationed or demobilized in Britain, the racists also targeted their partners and spouses who were often white women. In response, at various intervals in Cardiff groups of whites that had formed lynch mobs found themselves in shootouts with the racialized people they tried to target.

In 1948, in Liverpool the National Union of Seamen strived to keep Black people out of work, boasting that “we have been successful in changing ships from coloured to white, and in many instances in persuading masters and engineers that white men should be carried in preference to coloured.” During an extended period of attack, Black sailors armed themselves to stave off attempted massacres by mobs of whites either in uniform or in plain clothes intent on destroying them, the lodgings they stayed in and the clubs they frequented. Often when the police ‘“intervened” in racial attacks on Black sailors they’d simply arrest every Black person in the area.

In 1958, the West Indian community of Notting Hill tooled up to fight fascists who’d been targeting them at night, utilizing ambush tactics and skills many had gained in their time in Britain’s colonial armed forces. One ex RAF mechanic, Baker Baron was interviewed years later and said;

“[…] black people were so frightened at that time that they wouldn’t leave their houses, they wouldn’t come out, they wouldn’t walk the streets of Portobello Road. So we decided to form a defence force to fight against that type of behaviour and we did. We organized a force to take home coloured people wherever they were living in the area. We were not leaving our homes and going out attacking anyone, but if you attack our homes you would be met, that was the type of defence force we had. We were warned when they were coming and we had a posse to guard our headquarters.

When they told us that they were coming to attack that night I went around and told all the people that was living in the area to withdraw that night. The women I told them to keep pots, kettles of hot water boiling, get some caustic soda and if anyone tried to break down the door and come in, to just lash out with them. The men, well we were armed. During the day they went out and got milk bottles, got what they could find and got the ingredients of making the Molotov cocktail bombs. Make no mistake, there were iron bars, there were machetes, there were all kinds of arms, weapons, we had guns.

We made preparations at the headquarters for the attack. We had men on the housetop waiting for them, I was standing on the second floor with the lights out as look-out when I saw a massive lot of people out there. I was observing the behaviour of the crowd outside from behind the curtains upstairs and they say, ‘Let’s burn the niggers, let’s lynch the niggers.’ That’s the time I gave the order for the gates to open and throw them back to where they were coming from. I was an ex-serviceman, I knew guerrilla warfare, I knew all about their game and it was very, very effective.

I says, ‘Start bombing them.’ When they saw the Molotov cocktails coming and they start to panic and run. It was a very serious bit of fighting that night, we were determined to use any means, any weapon, anything at our disposal for our freedom. We were not prepared to go down like dying dogs. But it did work, we gave Sir Oswald Mosley and his Teddy boys such a whipping they never come back in Notting Hill. I knew one thing, the following morning we walked the streets free because they knew we were not going to stand for that type of behaviour.”

In 1959 Kelso Colchrane, a Black Antiguan resident of Notting Hill was stabbed to death by whites, in response Rhaune Laslett, Claudia Jones, Amy Ashwood Garvey and other revolutionaries put on an indoor Carnival to empower the besieged Black communities of Britain. With time, these gatherings grew so large they out-grew the halls they were held in and were the groundwork to what is now a cultural institution for the West Indian communities in Britain. The Notting Hill carnival.

In 1968, Trinidadian revolutionary Frank Crichlow opened the Mangrove restaurant which quickly became a hub for Black people to seek shelter from the racist hellscape around them and organise their fight back against the British state. In fear of this, the police raided and shut down the restaurant a dozen times. Attacks like this against Black community centers, cafes, clubs and even daycares were surprisingly common.

In 1970, 150 Black radicals protested against the police’s war on the mangrove and were met with a force of over 600 police officers, who assaulted the marchers leading to the arrest and trial which would later be known as the Mangrove 9. They won in court after a long trial and the police’s assault on the Mangrove carried on until the 80s, in 1988 Frank was framed after riot police raided the restaurant and ‘found’ drugs. After a trial he was acquitted and was awarded damages in 1992.

Throughout the 70s the Bengali Housing Action Group, the Black Panthers & Race Today collective squatted homes to house immigrants in spite of the racist local government & landlords.

Brixton was a borough plagued by policing and constant searches under the racist ‘Sus’ laws, enabling the police to stop and search people whenever the hell they felt like, this tactic was paired with arbitrary raids, beatings and surveillance. This was responded to in a myriad of ways; Black power organisations set up infoshops and educated their peers as part of a broader campaign against police harassment. Some squatted in buildings to drink smoke and listen to reggae in spite of the police. Some would intervene with the police when they began to harass someone.

In 1976, an 18 year old engineering student, Gurdip Singh Chaggar, was stabbed to death. The Indian Workers Association [Southall] organized a meeting on facism, but the youth attending the meeting grew frustrated with the “timid” bureaucratic, lobbyist approach of their elders and the lack of a concrete response to Chaggar’s murder. Opting instead for direct action, they left the meeting to protest against Southall’s police for its inaction, and in the process ended up throwing stones at a Jaguar who’s driver called them “black bastards”. Shortly after, they launched the Southall Youth Movement (SYM). In the days that followed, they organized a number of protests, attacked white motorists who chanted racist slurs at them and when their comrades were arrested, surrounded the police station demanding their release. These new formations would be later described by Race today as “breaking through the solid wall of Asian organisations which maintained the status quo”

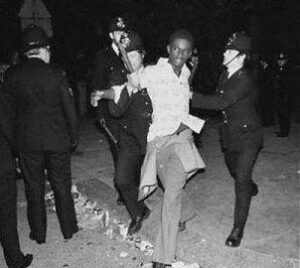

August, 1976, police assaulted Black attendees of the Notting Hill Carnival and they defended themselves and injured over 300 police officers, damaged 35 police vehicles and looted shops. The repression that followed led to the arrest of 60. Rasta Billy, a former steel pan player at Carnivals commented that;

“Carnival became the first opportunity that many of the black youths born in Britain had to express their anger on a national basis and to confront the police and let them know the forces of black anger.”

In 1980 Akhtar Ali Baig was brutally murdered on East Ham high street by a gang of white, skinhead youths aged 15 to 17, who first verbally abused him before spitting on him and eventually stabbing him. Paul Mullery, the one who stabbed him exclaimed in front of eyewitnesses “I’ve just gutted a paki!” He was soon arrested, In response 150 Asian and some West Indian youth marched to Forest Gate police station, the police claimed it wasn’t a racially motivated attack. Later 2,500 people marched through Newham in a protest organised by Newham Youth Movement, they planned to march to Forest Gate and West Ham police stations and then return to the murder location, the police tried to re-route them towards West Ham Park but the youth broke through chanting “Here to stay, Here to fight!” and “Self Defense is no offense!” On reaching the site of the murder spot, the march stopped to pay its respect to Akhtar. A mullah chanted some prayers from the Koran There were 29 arrests and in response the youths met with the Steering Committee Of Asian Organisations to drum up support and put on a second march, 5,000 people attended, Black workers from Ford’s downed tools and (in a rare, minor, piece of middle class racial solidarity) shopkeepers shut their shops for the day.

April 10th, 1981, the boiling tension following the racist mass murder of 13 Black teenagers in the firebombing of a house in New Cross into an anti-police insurrection, Michael Bailey, a Black man who had just been stabbed in Brixtons ‘frontline’ was being kneeled on by police for over 20 minutes. People nearby intervened and forced the cops away from him and took him to hospital, they then fought with the police reinforcements that had been sent in. The following day, the police lined the streets every 50 meters with vans, rather than their usual foot patrols. Word got round that Michael had died in hospital, no small part due to the police allowing him to bleed out for so long. At 5pm a plainclothes cop was bricked for trying to search a Black man’s car, police attempted to arrest the bricklayer but eventually battle lines were drawn. By the end of the night there were 279 injured cops, 50+ destroyed police vehicles and several buildings and shops burnt out and looted.

July 3rd, 1981 three coachloads of white skinheads from the East End arrive in Southall for a gig at a bar called the Hambrough Tavern, on the way there they attacked shopfronts run by Asian people and assaulted one Asian woman, in response Asian and West Indian youth struck back, the police came in to defend the skins but by the end of the night the skins were sent packing, several police officers were injured and the Hambrough was burnt to a crisp. The youth said to the media the following day;

“If the police will not protect our community, we have to defend ourselves.”

Throughout July 1981 There were further anti-police and anti-racist uprisings in Toxteth, Moss Side, Chapeltown and again in Brixton. There were so many I’d run out of space if I covered them all properly.

1982, The Sari Squad, a group of radical South Asian women began their campaign in solidarity with Afia Begum who had been deported to Bangladesh after her husband died in a fire. They established a social center in London’s Brick Lane. The following year they would tie themselves to the railings outside the home secretaries home, they were later arrested and sexually assaulted by the police.

In 1983, a collective of diasporic South Asian women founded Mukti magazine, with the intention of creating a publication to address the under-discussed concerns of South Asian women in the (politically) Black movement of the time. Topics such as deportation, citizenship, sexual fulfilment, lesbianism, arranged marrage, incest and child sexual abuse were presented in 6 different languages. They had a wheelchair accessible office and hosted meetings for groups like the Incest Survivors Group, Asian Women Youth Workers Group, and Aurat Shakti exhibition group.

September 1985, armed cops had gone to Cherry Groce’s home, in Normandy Road (Brixton), to find her son, Michael, who was wanted for armed robbery. Mrs Groce said the cops rammed down her door and then ran at her pointing a gun, she moved backwards and they shot her. She was paralysed and confined to a wheelchair by her injuries. In response people mobilized outside Brixtons police station and a group of Black women cussed out the police, it wasn’t until the police wheeled out a ‘community leader’ and a Black priest intended to deescalate the situation that the molotov cocktails began to fly.

December 13th 1995, another Black uprising took place after the murder of Wayne Douglas, in police custody. Black lumpen and their mates fought back against police, ransacked shops and burned cars for five hours.

December 1999, five Chinese restaurant workers, who had had to defend themselves against a white attack in London’s Chinatown, were themselves arrested. (This incident is a repeat of what happened in a similar attack in the same restaurant 13 years prior)

June 5th 2001, in Harehills, Leeds the South Asian community stood up to the police who had beat a South Asian man for having a “faulty tax disk”, they organised an ambush using a hoax 999 call, ironically reporting that a police officer had been struck with a molotov cocktail, the police arrived and the insurgents threw molotov cocktails and stones at them and fought the police into the night for their friend.

In August 2011, a young Black woman initiated the Mark Duggan Rebellion by throwing stones at a crowd of police who were looming around at a vigil for Mark, the police responded by beating her and the crowd rushed fight them off, the crowd, in control of the streets started to loot shops, that summer the whole country burned. Only after a police crackdown of an unimaginable scale combined with meddling leftists & the Black liberal counterinsurgency did the flames die out.

In 2016, London Black Revolutionaries and the Malcolm X Movement released insects into a Byron Burger restaurant in response to the Chain conspiring with border force in a sting operation which led to the deportation of 35 migrant workers from Albania, Brazil, Egypt, and Nepal.

In 2021, a collective of radical Black squatters called House of Shango, inspired by the legacy of Black revolutionary and squatter Olive Morris distributed free food and clothing every Sunday in Windrush square.

In 2022, the government warned of a coming economic crisis of their own creation, in response Autonomous Black Queers distributed free guides on shoplifting, fare evading and electric-meter tweaking.

On top of all of this, we can’t forget the prison rebels who fought against racism on the inside in our past like Biba Sarkaria or the countless more that have carried on the tradition since. There are of course, daily little resistances, fights, scuffles, people slacking off at work, stealing from the businesses robbing us of our money and time.

On the 18th of July this year, in Harehills, Leeds; children were kidnapped from the home of a Romani family by police on the orders of social workers. In response the community came out and fought the police demanding the children be returned, into the dead of night, successfully fighting off riot police. Bonfires were lit to obscure the police’s line of sight, though one was extinguished by Mothin Ali, a green party politician who actually mentioned his uncles getting repressed following the 2001 harehills uprising as the reason why he and his cohort acted as a counterinsurgent force. The following day the parents went on a hunger strike and days later the children were released back into their care.

In November last year, viral misinformation following a stabbing was spread on telegram by fascists in Ireland, raising the temperature just enough that the pre-existing racism, anti-blackness and Islamophobia amongst the white Irish lumpen, working, middle and ruling classes could boil over into an attempt to stalk the city center, jumping anyone darker than a sheet of paper. They failed, with the 2nd night going out with a whimper, rather than another bang.

In England, Cornwall, Wales, Scotland and “Northern Ireland” we weren’t as lucky. Starting in Southport, then spreading to other towns and cities. This wave of white violence resulted in assaults on racialized people, stalking of racialized people, the destruction of buildings used to house refugees, personal and private property belonging to racialized people from homes to shopfronts, cars to community fridges and numerous attacks on mosques.

The British state, under supercop Keir Starmer’s “patriotic” & “left wing” leadership, gave us ever increased police powers, the further criminalization of self defence, mask bans and the familiar high speed court processes Kier was a part of as a prosecutor during the Mark Duggan Rebellion in 2011 leaving antifascists with little time to defend themselves in court and the use of the charge of ‘Affray’ which was created to curtail anti-police street militancy by the Black communities of London has been utilized again to a great extent as a tool of repression.

Labor and Green party politicians and their supporters attended some protests with the sole purpose of preventing anything other than newspaper sales happening. After all, for many of them it was the first time “the left” were in power during a period of unrest and of course, we can’t upset the police when they’re ‘on side’ right?

The extra-parliamentary Left complemented this with the near-immediate Trotskyist-led dampener on resistance, a well-rehearsed program of peace policing, often going as far as standing between the police and militant demonstrators, standing in front of targeted buildings for photo-ops and then bailing when the fascists turned up. Leading people the wrong direction (both literally and figuratively) selling newspapers while projectiles were being lobbed at them, a counterinsurgent politic culminating in a collaboration with a group of washed up social democratic politicians hosting a ‘resistance festival’ of white people patting themselves on the back for spending weeks bussing themselves into London to talk to the police.

Finally and in the most depressing, but not at all suprising display of all, Many “radicals” in the “POC, BAME & ESEA” organising circles joined forces with the assimilationist middle class in advocating ‘staying at home’ and staying “safe” and working with the police to utilize hate crime legislation to encourage even more police into our neighbourhoods.

The antifascist response to the race riots this summer was sluggish in places, most were blindsided by the sheer number of whites willing to march around in broad daylight chanting racist & islamophobic slogans and how many white youth were willing to smash the windows of peoples homes because they believed the residents weren’t white enough. However once the ball got rolling, the fightback that ‘organised’ autonomous anti-fascists and racialized communities across the country put back were awe inspiring.

Crowds of teenagers ignoring the warnings from the peace policing ‘community elders’ donning what is essentially black bloc and confronting fascists in the streets, traveling to support communities in other towns in response to fascists announcing plans to march in towns all over the region. People forming networks of support for vulnerable members of their communities, providing each other with transport and even seemingly trivial things like checking in on each other on the regular.

However, former Black Panther, JoNina Ervin’s comment in an interview a few years ago about how antifascism can’t just be event based if it’s going to become part of the culture has stuck with me. We have to deal with how people are facing daily racism and daily policing. We have to create survival programs to help people live with the crushing living costs here.

Following the dying down of this round of race riots, radicals got to work supporting those arrested for defending themselves, for example; After this year’s Notting Hill Carnival, radicals, in the spirit of the original carnival, put on a fundraiser at an illegal rave, which raised £4000 in donations despite police repression.

Weeks ago Romani and Irish Traveler youth were targeted by Manchester police in a racially motivated operation and forced onto trains out of the city center. Soon after this, the Kurdish community in London were targeted by police repression with a community center being raided and dozens of people being arrested.

Bashar Al-Assad was overthrown days ago and in response the British state & states elsewhere are looking to deport Syrian asylum seekers into an active war zone as the civil war and genocidal campaign against Syria’s ethnic minorities, aided and backed by the Turkish state and its fascist proxies is nowhere near over.

Throughout the history of the struggles of racialized people here, there has been an insurgent tendency who have rejected the pacifistic stewardship of middle class & reformist political groups who constantly have worked with the police and the government to assert themselves as self-declared ‘leadership’ of their respective cultures and nationalities.

Our aim as a group is to amplify the voices of this tendency, with the race riots this summer and the response to it being a catalyst for us to come together. Many of us are either one of the few anarchists in our culture’s diasporic radical community or one of the few people who aren’t white in our local anarchist scene and as such there’s a need to create something without both of these restrictions, without having to water down anarchist texts into the often vague language used by sectors of the Asian and Black radical movements or to have our thoughts filtered through the all white editorial boards in charge of the majority of anarchist publications here. Are you doing cool shit, have something to say, knowledge to share? Let’s work together and burn Babylon once and for all.

Mutt, Muntjac Magazine

13/12/24

“Mutt.” is a pen name of a Bajan Mulatto anarchist, you can find more of his writing and research on his website. Stalk his stuff here; linktr.ee/muttworks