I deleted “space” off the title and replaced it with “context”. I am sick of “space” being used as a vague word to describe everything from industries to rooms. Let us be more specific!

Indeed, I crave specificity, but I am afraid I did not do justice to my desires recently, when I shared a warm university room to discuss criticality and politicised engagement within ESEA spaces.

The thought that weighed on me was this: I should not have been there. Someone from Kanlungan or a solidarity group should have been there. A staunch trade unionist, a seasoned organiser. I keep wanting to spill out my insecurities, explain my identities and experiences and credentials, but that individual egotistic self is part of the problem. Boring. You don’t need to see my insides, what I am saying needs to hold up and that’s that. Why the fuck am I worried that I didn’t do a good job when it’s ludicrous that I can grift around like this in the first place?

Let’s call this self-criticism. I’m sick of thinking about my career and hearing about others’ careers. That is not the same as discussing labour conditions.

I wish I had been braver and said something like this from Being In The Room Privilege by Olúfémi O. Táíwò:

The facts that explain who ends up in which room shape our world much more powerfully than the squabbles for comparative prestige between people who have already made it into the rooms. And when the conversation is about social justice, the mechanisms of the social system that determine who gets into which room often just are the parts of society we aim to address. For example, the fact that incarcerated people cannot participate in academic discussions about freedom that physically take place on campus is intimately related to the fact that they are locked in cages.

When I leave the university room someone else is gonna clean it.

I should have said very simple things like: disabuse yourself of the notion that spectacles of mass will free anyone and escalate your actions accordingly. We must continue to resist immigration raids. If a support role is more your capacity, join your local copwatch network. Sign up for arrestee support and Legal Observer training. Look out for all the participants at your local encampment. Ensure you’re attending to the material and emotional needs of people abandoned and vulnerablised by the state, which at times means risking your job if you have mandatory reporting duties. Like my friend Kirstin said, we need to recognise that in this moment we’re opposing fascism. Let’s act like it!

*

At the launch of Rifqa last year, one of my editors, Brekhna, asked Mohammed El-Kurd about the importance of representation. He began his answer with ‘Well, what are we representing?’

Can we get real about answering this? What do our frameworks allow us to see and prioritise?

*

I know I am just saying words. Typing them, rather. I’m not under any illusions that we’re gonna post our way to liberation. We may for example talk about who gets to access and control digital space but what does that mean? Certainly an audience member was correctly and excitingly sceptical, especially because we drifted away from a question on future organising. But I still return briefly to this topic because I want to use this as an opportunity to insist on specificity of language. By “access to digital spaces”, do we mean instagram reach or fibre optic cables being bombed? We have seen how the state can and will institute blackouts and how our phones are absolutely full of incriminating data–and these devices are of course produced through minerals and labour extracted from the bodies and earth of the Global South–so we need to bring about organising and information security which does not rely on our current technologies. I recall from an anarchist forum that there’s someone at 56A infoshop interested in this.

In the context of resisting state violence, visibility is simply not the goal. When we talk about “seeing ourselves” maybe what we’re really talking about is liberal spectatorship, of spotlit role models rather than the practicalities of avoiding state surveillance and intervening against racialised hypervisibility. What would our conversations look like if, to gloss A. Sivanandan, we interested ourselves in the racism that maims and kills? I simply cannot understand why “representation” on the screen and stage is described in explicitly existential terms while multiple genocides are being carried out by the imperialist project of the West. I reject such a framing with my lungs, heart, and teeth because I know a lack of theatre roles is not starvation, dispossession, martyrdom. We are misrepresenting state violence by eliding genocide with arts careers.

Of course in theory these are not irreconcilable positions (i.e. you can be active about representation in the CCIs while also mobilising against state violence). You don’t need to pick up a weapon to be a revolutionary figure. Culture itself is a site of struggle. As Louis Allday writes, Ghassan Kanafani and the late Refaat Alareer fought the Zionist entity through their revolutionary art and cultural criticism and were martyred for it. This is because they understood the seriousness of the struggle on the cultural front and acted accordingly. In his introduction to the 2022 English translation of On Zionist Literature, Steven Salaita writes:

Kanafani was a searing and incisive critic, at once generous in his understanding of emotion and form and unsparing in his assessment of politics and myth […] Anything that threatens centers of power earns the label of “political,” perforce a negative evaluation, and the disrepute that comes along with it. Power therefore comes to embody the apolitical. This sort of environment is unwelcoming of critics such as Kanafani.

These writers did not desire a vague representation or to rise through the ranks of imperialist cultural industries, but what they wrote about and how they shared that work furthered the cause of Palestinian liberation, the Palestinian experience under the conditions of settler colonialism, building political energy and internationalism against the different faces of imperialism. That is existential representation!

Contrast this with how some ESEAs discuss the importance of representation. Think about the language we use to describe certain problems – I have noticed that a vocabulary filled with “representation” is inevitably accompanied by terms like “opportunities”, “competition”, “entering white spaces”, “bureaucracy”, “data”, “tick box”, “checklist” &c. What do these words allow us to see? Does a conception of “tick boxes” help us see who’s targeted to work the most precarious, dangerous jobs? Might we be able understand how certain jobs are criminalised by conceptualising work through “opportunities”? Can a reference point of “entering white spaces” open our understanding of how border securitisation enforces white supremacy? Does “data” include challenging information-sharing with police, and can “bureaucracy” adequately describe the formalised xenoracism that migrants struggle against to secure their settlement here? We should get clear and honest with ourselves about the ideology attached to such language: neoliberalism, the slick reduction of all human life to the logic of the market. (N.B. yeah, you can beef with me about whether “neoliberalism” is a useful way of examining the irreducible nature of capitalism.)

Along the same lines, for the past few years, I have noticed a persistent circular reasoning behind the importance of representation–

- Representation is important because it’s representation because it’s important.

- There is a link between fictional representation and real life therefore representation is important because it’s linked to real life.

- We need to change things through representation in bureaucracy so bureaucracy can change because of representation.

- We need to be represented in data so we need to collect data so we can change things because it’s important and it’s important to change things so we need to collect data to be represented in data to be–

–and so on. Round and round it goes, like a washing machine.

To speak of data, have we noticed that this vocabulary of “over-” or “under-representation” is the language of data analysis and policy work? For example, “ethnic minority over-representation in the criminal justice system” is office-speak for police violently targeting Black populations (in itself a genocide). Which do we think more appropriately registers what is at stake here? Does a language of representation force non-Black Asians to reckon with our role in counterinsurgency through anti-Blackness, normalisation of zionism, our currently inadequate opposition to police intervention for “Asian hate” and hate crime data collection (in itself criminogenic, as Dylan Rodríguez notes)? Of course not. Because the point is to just see ourselves, only ourselves. This vague language fogs up the mirror so we can shine it clean, brightening our own image.

Saturating conversations in any and all contexts with the language of representation advances the ideology and class interests of liberal ESEA professionals as the solutions to the problems they’ve identified are, in essence, improved career opportunities. The representasians will write the books and papers and screenplays, perform roles centred on their stories, organise rallies with police support, get the research funded and present it, tour the speaking circuit, facilitate workshop after workshop–which, of course, implicates myself and most other freelancers working this grift. I can criticise and complain and invoke my working class parents and my state school education–and I am still in that room.

Afterwards, when I’ve pretend to know anything about anything, I will get love2shop vouchers worth fifty quid because I have done my job. Then, long after I’ve gone home, outsourced cleaners will do theirs.

*

The more specific and detailed your group objectives are, the less it matters if you disagree about other things (generally speaking & caveated to all hell). If you’re never specific, then you never have to show your discernment.

This feels like the appropriate point to bring up a major rupture in ESEA organising which I feel has not yet had adequate public discourse. The wound has festered. I had thought of bringing this up during the panel talk in answer to whether or not the “ESEA space” had changed or what we could do differently in the future, but I didn’t trust myself to verbalise these sensitive details, so I will share it with you now in writing.

On June 21 2021, Remember & Resist, my friends who organise against state violence by advancing the abolitionist project in ESEA contexts, released their full statement on the fallout of the Demonstration of Unity, a rally organised by ESEA groups intended to take place the previous month. The event disintegrated due to a lack of transparency, accountability, and commitment by some of these other groups, especially around platforming a speaker, A. I first heard about the legal issues in 2017, and his former partners and their supporters were still struggling against a defamation case brought by him 4 years later in 2021, coinciding with the Demonstration of Unity.

I emphasize this timeline because harassment and abuse eats up so much time and hearts and bodyminds. Abusive behaviour is enabled over the years by a whole raft of interpersonal and legal structures. It simply doesn’t go away if you ignore it or silence it; the resulting and deliberate implosions pull in new targets, not just people but anything we might try to create, since what we’re able to make is the sum of our relations, not the product of individual genius. Even its second- and third-hand effects are deeply felt. Abuse parasitises the political energy, care, and compassion we so urgently need to nurture. In organising contexts this is compounded by treating survivors and their supporters like troublemakers, telling us we need to set aside “personal problems” so the big stuff, the real problems, can be solved. There are key ideological and practical reasons why this is absolute nosense. We cannot wait until later to resolve abuse because abuse itself obstructs effective organising. Resisting abuse of power in all its forms is integral to the struggle. As grassroots research by Salvage Collective shows, in practical terms the outcomes are consistently the same: the people (usually men) remain in positions of power, groups close ranks around them to protect themselves and isolate survivors and their friends, who are inevitably pushed out. This is so that financial and social capital, access to employment on projects / campaigns / events / services, public platforms and venues and other sites of organising & production &c are still controlled by the core group(s), ensuring nothing is redistributed.

This is how it happened in long-established leftist organisations such as the SWP and MFJ. This is how it happened in the nascent conglomeration of groups claiming to progress ESEA causes. The dismissal, victim-blaming, and harassment compounds the burnout of organising. So when I hear others say that we’re being too harsh on ESEA groups or that “just like other groups” we need to have agreement and unity to get things done, it makes me wonder what we’re actually doing here. Because we’ve already shown that “just like other groups” we’re capable of actively creating unsafe spaces for survivors and anybody else who struggles against sexual violence and abuse of power. Since a key tenet of ESEA rhetoric (such that it exists) is insisting on our victimhood and innocence, this reads to me as a reluctance to own our potential to cause harm just like anybody else. “Calling out”, disagreement, and conflict are presented as problems-qua-problems, but exactly what they’re “calling out” &c is left vague, a magic trick: presto! Complainants become malcontents and we never get round to tackling the pre-existing power structures and group dynamics. Such repeated experiences would make anyone angry, impatient, exhausted. Can we grasp that all at once? To think through Audre Lorde’s uses of anger, do you refuse to listen because my tone is harsh or because you’re afraid my words contain information that will change your life?

*

Returning to the statement by Remember & Resist, I encourage close attention to this footnote:

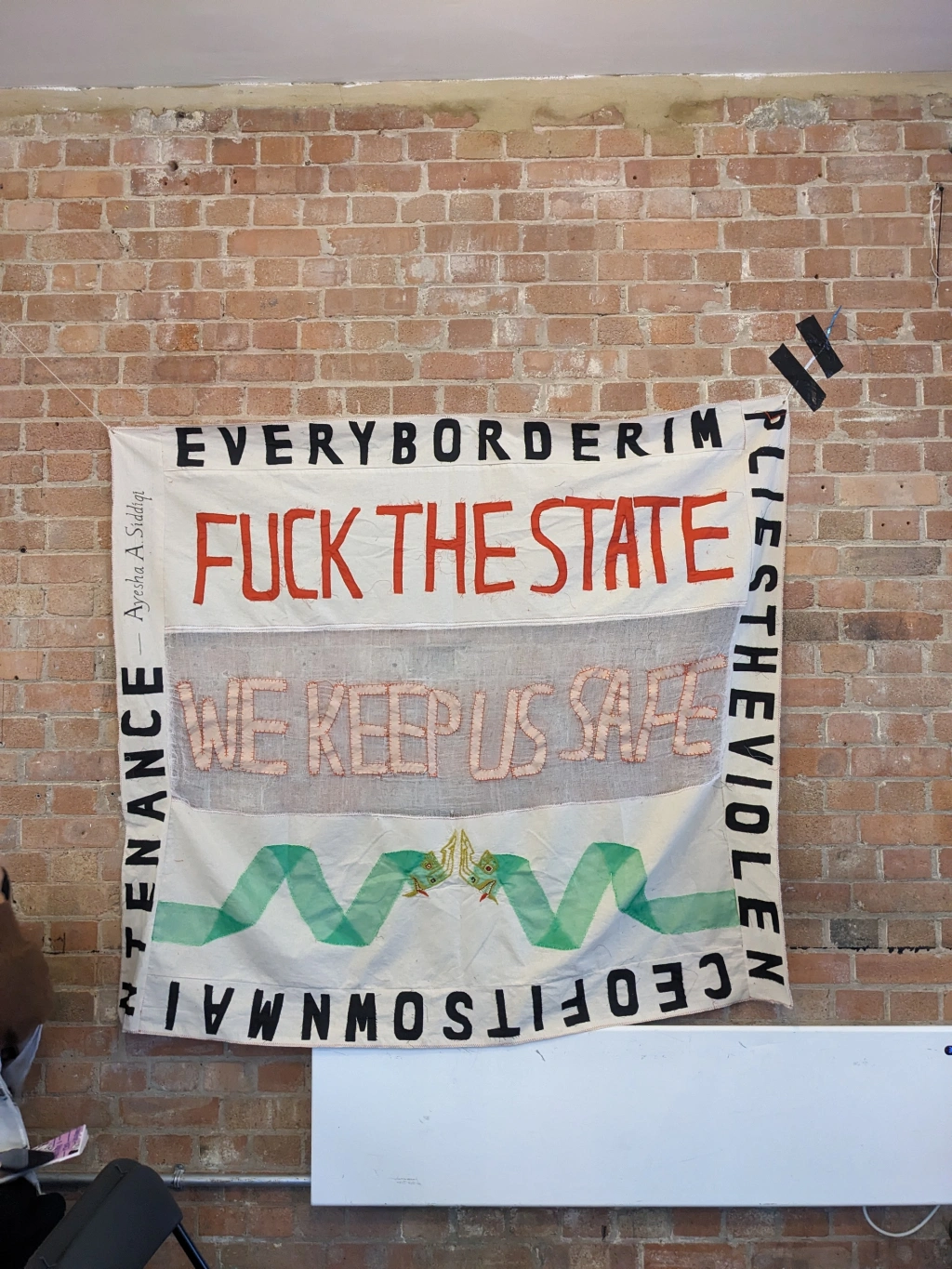

Some groups decided to call for a strong police presence to “ensure safety” of attendees unaware of the cancellation, which led us to have to coordinate legal observers the night before.

This encapsulates the failure of certain liberal ESEA groups to understand the disciplining role of state violence, whether it’s the HKPF or the Met. If we heed the call to view racism through a lens of state-sanctioned predilection to premature death (vide Ruth Gilmore Wilson), and we understand the police as violent protectors of bourgeois colonial interests empowered by the state to kidnap, detain, violate, maim & cause death with impunity, then… what does it mean when we call on such forces to protect a demonstration on “ESEA unity”, if not capture of the identity by reactionaries? What did we need to be kept safe from, when it was members of our own community that said and did harmful things?

In co-ordinating legal observers in advance, the members of Remember & Resist did more to practically advance the cause of “unity” than anyone who insisted cops could keep us safe. As Kevin Blowe from Netpol wrote in his call for solidarity not service provision, this forward planning is in itself a form of relation, of co-operation rather than prioritising a big demonstration and leaving overstretched volunteers to pick up the pieces later.

Four years on, little has changed. The British ESEA liberalism held by certain groups is so trapped in its own image that a spectacle of mass is prioritised over informed and practical deployment of any meaningful organising, learning nothing from recent struggles against state violence from within / against Asian contexts, from abolitionist feminist practices, from Palestinian liberation movements and their repression in the west.

*

But I hear you protest: we really are learning! please don’t shout at us, we’re trying ever-so hard! And perhaps, indeed, we are not so different. In my early radicalisation from liberalism, I agreed with the need to decolonise and admired decisive protest action—but I also viewed it all as “activist stuff”, actions that were probably secret and specialised that you had to be very brave to do, and that my struggle (fighting in online comment sections about whether a book and its author was racist or not) was also important. I actually believed that we were each advancing an anti-racist cause, we were just doing it in our own way, from our own positions. Then I started volunteering with local queer creative groups, and quickly learned that the struggle against racism, gentrification, homelessness, criminalisation, institutional transphobia, policing, poverty, borders &c needed to approached all at once. The police aren’t just out on the streets, they’re in our safeguarding practises and community centres. I had to learn quickly that the state has been explicit in its intentions to create targeted harm in the name of order, and that we need to actually see the state as it is, not how we want it to be, in order to come up with practical solutions to meet people’s needs. We can’t afford to be trapped in an image.

And I hear you say, But we can’t do everything at once, do you want us to BURN OUT? What about OTHER GROUPS who all agree on things to do stuff, why can’t we just agree as well? Do you want us to be PERFECT all the time? I ask you, where in anything I have said or written have I ever demanded perfection of you personally—and do I have the power to not only ask that of you but somehow enforce it? And where are these other mythical groups with perfectly aligned beliefs? To draw on my experiences in queer community, we have had to actively & collectively (amongst many things) combat transphobia and gentrification and police in our social services and arms manufacturers at Pride! So I’m not picking unfair targets, I am in fact trying to be consistent. (Which probably then prompts certain people to say, But surely our situation is different. Round and round it goes, like a washing machine.)

I believe it’s past time to be honest that there are irreconcilable positions within ESEA groups. We’re not struggling from different places and we actually do not want the same things! Why soften that? It goes beyond a matter of disagreeing on what we feel should be prioritised: some of us want to decisively oppose state violence and imperialism through coalitional struggle and creating spaces of mutual care, placing this as our political centre. That informs and energises anything we do, from art to support services to bricks thrown at weapons factories (which I know nothing about, obviously). And some of us want better representation in the census, screen, and stage, the whole world shrunk into a white space bounded by four straight lines, rather than reckoning with the intimacies of four continents. Sorry to pull out this by now corny paraphrasing of Marx, but surely the point is to change the world, not just interpret it.

Rather than seeing liberals as passively unradicalised, people who aren’t quite there yet, still learning, I find Dylan Rodríguez’s framing of militant liberalism to be clarifying. Either own it or take up another position with firm intentions, contextualised according to our specific skills, knowledges, and communities–and have the humility to know when we lack this range, accept conflict & join already existing movements where applicable.

What if you look at where you already are and what you’re already doing, and try answering the following question: What would it mean for our practices to start at the point of resisting, critiquing, and analysing state violence?

[Changes: 08/06/2024 small edits for typos, clarification, phrasing]