In 1958, at a pub in St. Ann’s, Nottingham, police were called in response to a disturbance. Eyewitnesses reported that it all kicked off over the refusal of service to an interracial couple, sparking a brawl. Some say over 1,000 people were involved; others put it in the hundreds. Either way, chaos filled the streets. If you look at the newspapers from the time, it’s all about “Black violence” and how many white people were injured. But here’s the thing—the evidence points to much of the violence being led by a white mob.

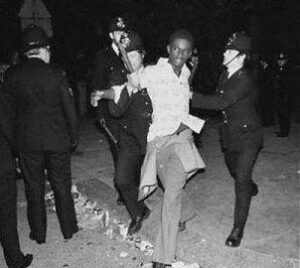

Let’s be clear: this wasn’t a race riot like they like to call it, this was a fascist attack, a pogrom. Black people who were there say white individuals from outside St. Ann’s showed up, forcing the community to fight back and protect themselves. The participation of potentially hundreds of white individuals was historically downplayed. Only through community accounts and extensive archival research has it become possible to uncover a clearer picture of what really went down. Another overlooked aspect is the prolonged police presence—sticking around for weeks afterward.

A few days later, another uprising happened in Notting Hill, some say that this uprising was spired on by the happening in Nottingham, where black forks had managed to fight off a racist mob. These encounters with white reactionary violence mark a pivotal time in the black experience in Britain.

This happened ten years after the first voyage of the Empire Windrush. The early immigrants of color in the UK tell a story of exclusion. Caribbean immigrants faced serious barriers to housing and employment, despite being invited to Britain to address labor shortages after World War II. They ended up making homes in cramped Victorian terraces, originally built for mill workers. While the country relied on immigrants, they were treated like outsiders, unable to access social spaces freely, unable to participate fully in society.

The Colour Bar in Britain worked like an informal apartheid, denying Black and brown people decent jobs, housing, and public spaces. It lasted in one form or another into the 1980s. Beyond that, they struggled just to have a normal community life.

And then there were the Teddy Boys—a racist gang emerging from white working-class youth culture. They harassed Black and Asian immigrants, making it dangerous to access certain areas. People who lived through it say this kind of intimidation carried on into the ’80s. Let’s face it: that same culture seeped into the punk scene of the 1980s. If you’ve ever seen This Is England, you know what I mean.

Through self-defense and resistance, Black and brown communities carved out their own safe spaces. They stood up against violence and refused to accept their assigned place in a racist hierarchy. It is not a coincidence that the conflict arose from the refusal of service of a interracial couple. It’s obvious that reactionary violence is tied to the insecurities of white working-class social conditions, tools used by those in power to spawn hate against marginalized groups. For black and brown people in the UK, Self-defense and rebellion became liberatory tools—to protect the community, to demand better treatment, and to push back against structural barriers enforced by the state.

So maybe we need to rethink the language we use. Instead of calling it a “race riot,” we should recognize it as a form of uprising, a rebellion, a moment of resistance. “Race riot” plays into the same old narratives that pit both sides against each other. Let’s call it what it was: an act of resistance.

Sources:

blackpast.org/global-african-history/nottingham-riots-1958

bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-nottinghamshire-45207246

libcom.org/article/1958-nottingham-race-riots